“It’s not a cookbook,” I explain patiently (yet again) to someone at a book signing for my first book, “A Culinary History of Myrtle Beach and the Grand Strand.”

Yes, it has about a dozen recipes – and you’re going to get a great one at the end of this article – but it’s a history book. And not a boring old dry history book either. This one is full of juicy and succulent historic morsels.

John Blake White’s painting titled “General Marion Inviting a British Officer to Share His Meal” features sweet potatoes.

Colonial women were tough old gals. They produced meals and prevented food from spoiling in those days before refrigeration, which was no easy task in the South Carolina heat and humidity. That humidity prevented them from preserving much beef (pork was easier to salt and keep) or making any hard cheeses. They did enjoy a soft cheese called clabber, which was essentially spoiled milk left out to thicken into a sponge-like gel.

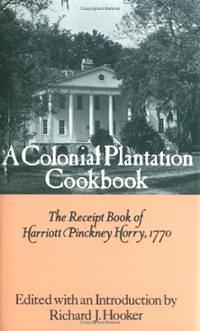

But despite the challenges, they managed to create many tasty dishes. We’re extremely lucky that Eliza Lucas Pinckney (1722-1793) and her daughter, Harriott Pinckney Horry (1748-1830) left many of their recipes for us to marvel over and recreate…or not.

In “To Dress a Calves Head,” Horry provided many steps and ingredients, starting with boiling the head “till the Tongue will Peal” and ending with making “little Cakes of the Brains and dip them in and fry them,” before the head is plated with oysters, brain patties, the tongue, bacon and forcemeat, garnished with horseradish and barberries. Another calf’s head recipe said “To dress a Calves head in imitation of Turtle” is a soup containing chicken in addition to the head.

But this same family also ate muskmelons, walnut and mushroom catsups, quince marmalade and cakes flavored with mace and rose water. They also had a huge fondness for puddings, with flavors from apple and orange to carrot and yam.

In the Civil War era, they learned to make risen bread without yeast, apple pies with no apples, how to “cure” bad butter and preserve meat with no salt. However, puddings were still in favor. Even when supplies were running out, they still made puddings if they could scrape together four eggs, a pint of milk and a little sugar.

Today southern “nanner,” or banana pudding, is still a favorite and is a staple at pig pickin’s and oyster roasts. Even in Colonial times people who lived along the coast could purchase bananas rather inexpensively from ships that carried Caribbean imports.

As for those pig pickin’s, the slow-roasted pork was glazed with and accompanied by barbecue sauce, and often those recipes were closely guarded secrets.

In Georgetown, from the 1930s until he passed away in 1987, Wade O. “Buster” Camlin was known as one of the area’s best barbecue cooks. Raised in Williamsburg County as one of fourteen children of tobacco farmers, he learned at a young age the art of barbecue where wood was burned in a pit and then the coals were shoveled about every thirty minutes, all day long, under racks with hogs on them.

In his roles as a Shriner and a Mason, Camlin was the go-to guy for cooking several hogs at once for barbecue fundraisers.

“At one point, Daddy was cooking for 1,200 people at the Shrine Club,” said Buster Camlin’s daughter, Becky Ward Curtis. An undated newspaper clipping that Curtis has notes her father and his friend W.C. Hunter “once cooked barbecue for 3,800 persons during a S.C. Ports Authority affair.”

“He had barbecue pits at the restaurant [Camlin’s Restaurant in Pawleys Island, a site now occupied by a gift shop called Breathe],” said Buster’s son, Don Camlin. “When he cooked one time at Pawleys Island, he had a pit that would reach from here to the road with cement blocks for steps on the sides, with a metal rod across and hog wire rolled out. He’d leave a space along the sides to put the coals in there. He got Kraft paper from the International Paper Company and put that on top. He’d roll that paper back and use a kitchen mop to mop the sauce on, then put the paper back. He could cook forty pigs at a time.”

His sauce was renowned, and for 60 years people begged Buster Camlin for his recipe. It was a secret until Don Camlin allowed it to be published in “A Culinary History of Myrtle Beach and the Grand Strand,” and here it is for you. It’s easy to cut down the amounts for a smaller portion, and every time I make it, it turns out perfectly and coats the meat like a delectable dream.

Buster Camlin’s Barbecue Sauce

3 gallons vinegar

3 big (serving size) spoons black pepper

1 ounce red pepper powder

6 ounces Worcestershire sauce

3 big (serving size) spoons mustard

3 cups sugar

½ cup salt

32 ounces catsup

Blend ingredients and bring to warm. Do not boil!

Becky’s culinary history book and her second book, “Lost Myrtle Beach,” are available in the Myrtle Beach area at:

Books-A-Million

Barnes & Noble

Book Warehouse

The Horry County Museum

Brookgreen Gardens

North Myrtle Beach Area Historical Museum

Myrtle Beach State Park

And on the Web at:

Amazon.com

Barnesandnoble.com

Booksamillion.com

Beckybillingsley.com

Coming in 2015 is Billingsley’s third book, “Wicked Myrtle Beach and the Grand Strand.”

[wpdreams_rpp id=1]

Leave a Review/Comment